In a new age of modesty in literary and cultural criticism, Germanistik’s rich archive of theory offers exactly what we need to revive our critical engagements with the unrelenting information flows of the Internet age. The UC Berkeley German Department’s own PhD candidate Sean Lambert encourages us to not merely take it all in, but to “creatively disrupt.”

No one would say that critique is essentially German, nor that one must study German in order to learn critical theory. But there is a rich history of critique in German thought. In a contemporary academic world where scholarship must be interdisciplinary, multicultural and international in order to respond to a highly networked present, studying German opens up a rich archive of texts within the tradition of Germanistik that have always been at the intersection of philosophical, literary, cultural, historical, medical and theological studies (among others). German Studies is thus an excellent place to practice, not the Eurocentric, nation-bound critique of the past, but the critical theory called for today, which opens itself up to the world.

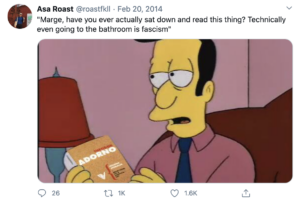

In our era of fake news, where simulated and “real” life have become practically indistinguishable, critique is more important than ever for examining the materiality of our virtual lives. However, in the past few years, critique — particularly of the dialectical kind — has come under fire within literary studies. Thinkers have favored methods such as surface reading or distant reading in contrast to Marxist or psychoanalytic methods, claiming that they better suit a world where violence, ideology, and the unrestrained use of power – some historical targets of dialectical critique – are all plainly on the surface. In one of my classes, students ask, in almost every meeting, if dialectical critique has “run out of steam,” or if we must “move beyond” it. Despite the fact that critical theory has always welcomed self-critique, and that “moving beyond the dialectic” seems, to me, a goal that requires dialectical thinking, recent scholarship and its echoes in this class have all contributed to what Jeffrey Williams calls, “The New Modesty in Literary Criticism,” in which critics, in a reversal of Marx’s famous aphorism, increasingly seek to describe the world, rather than change it.

German Studies has engaged productively with new modes of reading that forego suspicion (Eve Sedgwick’s turn away from a “hermeneutics of suspicion” comes just a few years after what David Wellbery called the “Post-Hermeneutic Turn” in German Studies), but studying German also gives us the tools to “rescue” dialectics in a moment where it seems in danger of being discarded. The Frankfurt School itself serves as an excellent example of the necessary endurance of critique. Whether writing about the naked violence of the Third Reich or the disguised, sublimated violence of the “fully administered world,” the thinkers of the Frankfurt School never took the legibility of the world’s surface for granted. A new Berkeley professor of Film and Media Studies, Rizvana Bradley, writes of a “resurfacing” that takes place in contemporary performance art about blackness. “Resurfacing” involves something of a paradox, both a quasi-suspicious reappearance of the suppressed humanity of raceless flesh beneath black skin, as well as the creative (though violent) re-making of black skin as a new surface for the body. German Studies today offers the opportunity, not to simply abandon dialectical criticism or reject “surface reading” outright, but rather to participate in a project of “resurfacing” that brings both to bear. This global, multicultural approach to critical theory by way of German Studies can creatively disrupt the surface of the world even as it attempts to describe it.

German Studies is not (by far) the only discipline where scholars can still train in critical theory or dialectical critique. But the rich archive of German texts that foreground critique makes it a vital site to keep critical theory alive and fresh. If we are to respond to the various catastrophes through which we are living, we must not content ourselves merely with considering the world’s surface, but rather participate in a project of resurfacing it. I take inspiration from Adorno: “thought is happiness, even where it defines unhappiness: by enunciating it. By this alone, thought reaches into the universal unhappiness. Whoever does not let it atrophy has not resigned.”