The first guest commentary in our Mission Possible series of hot takes on the purpose of German Studies comes courtesy of Dr. Albrecht Classen, Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of German Studies at the University of Arizona. His response to the question, “Why study German today?”, is an elegant reflection on the canonical legacy of German cultural history and its ongoing utility in the present moment.

This is the ultimate question relevant in our field, and very difficult to answer though we can certainly point to many general aspects: economy, politics, literature, philosophy, environmental protection, movies, sports, etc. They all matter critically in justifying the study of German today, but we should also not forget very personal approaches, such as the love for this language, love for Germany/Austria/Switzerland, or friendship and family relations, and passion for German literature. It would certainly be wrong to paint a rosy picture of any of the German-speaking lands and peoples, but we encounter in the German-language culture an enormously rich plethora of experiences, good and bad, profound ideas, concepts, and values, expressed in a huge treasure trove of poetry and prose from the Middle Ages until today.

In fact, many of the critical issues of great relevance in the modern world, promising or troublesome, have already been discussed throughout time by German-language philosophers, poets, theologians, and others. The discourse on love had set in already in the twelfth century, and missing out on Walther von der Vogelweide’s minnesongs (ca. 1190-1220) would be a serious loss. When reflecting on the meaning of death, i.e., the loss of a loved-one, it would behoove us to keep in mind what Johann von Tepl had to say in his famous Ackermann (ca. 1400). Reading through the famous Narrenschiff by Sebastian Brant (1494) still makes us laugh and realize the foolishness of most people, which quickly sobers us as to our self-perception today.

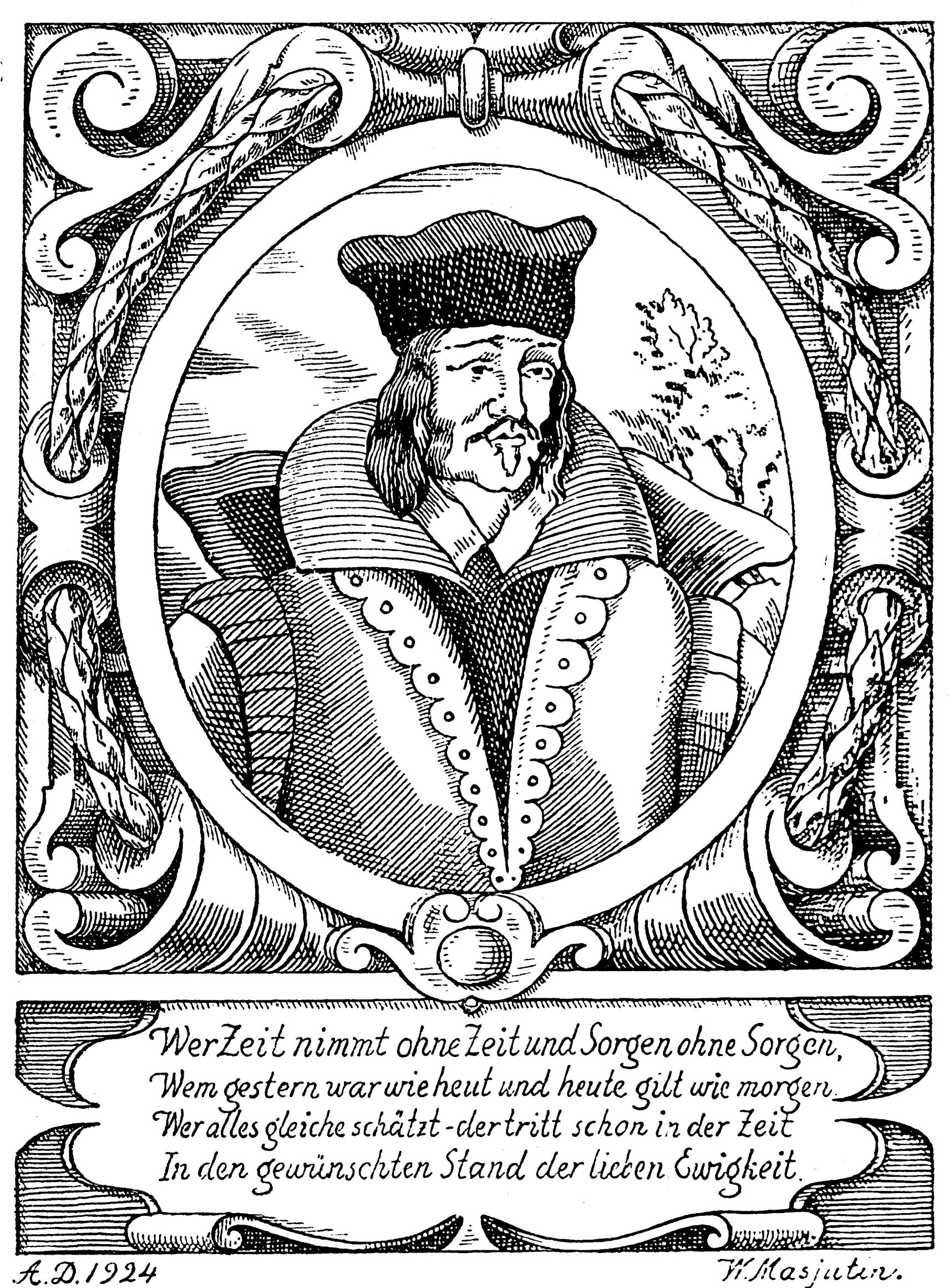

Some of the greatest revolutions or paradigm shifts took place on German soil, such as the invention of the printing press by Johann Gutenberg in ca. 1450, or the emergence of the Protestant Reformation, launched by Martin Luther’s 99 theses published in 1517. As the epigrams by Angelus Silesius (1624-1677) indicate, many of the ultimate questions relevant in all of human life were already addressed at that time, and found, to some extent, some mysterious answers by this Silesian poet. Human suffering in war, such as the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), led, surprisingly, to the creation of some of the best poems, the sonnets by Andreas Gryphius (1616-1664), while his contemporary Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg (1633-1694) formulated most intriguing poems about love, God, and death. Inquiring about the notion of tolerance already in earlier time, we only would have to turn to Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s Nathan der Weise (1779), where the protagonist is a living proof of this ideal.

The list of many other significant writers and poets, male and female, continues, and we would not need to pursue this argument further, though here I have used primarily a historical perspective. German Studies provides a critically important platform within the Humanities to examine essential aspects of human life, as expressed in many different media. Intriguingly, the current discourse on racism, anti-Semitism, colonialism, and imperialism can be traced back to many medieval and modern narratives, and then also movies. The contributions by German philosophers, such as Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) or Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), are universally acknowledged today as fundamental for contemporary theoretical issues, but our students must be able to read their works in German so they can learn the full meaning of their words, and understand the nuances and subtle messages. The entire field of modern theology is greatly influenced by the ideas and writings of German scholars, such as Karl Barth (1886-1968), but the same applies to the fields of sciences, medicine, astronomy, or optics.

Studying German does not mean that students would exclusively learn the German language. That is the basis, upon which then many forays into the deeper dimensions of academia and professional life become possible. Students with a B.A. in German Studies are ultimately highly qualified to partake effectively in the critical discourses of today, pertaining to the humanities and the sciences, and this from a historical and a modern perspective.